Disclaimer:

This post has been far too long in the writing - for which, apologies. The exhibition it discusses - Oscar Murillo's 'Violent Amnesia' , at Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, actually ended around two weeks ago. However, with another show currently on in London, and a lot of attention pertaining to his Turner Prize nomination, Murillo still feels very much like a man of the moment, just now. And to be honest, work like his is, in my opinion, worth discussing at any time. The Cambridge show certainly whetted my appetite for Murillo's oeuvre, and has inspired me to try to visit his London exhibition in the coming days. Perhaps this post will do something similar for you...

|

| Oscar Murillo, '(Untitled) Catalyst', Oil & Graphite On Canvas, 2018-19 (Detail Below) |

The painter and multi-disciplinary artist, Oscar Murillo seems to be gaining plenty of recognition, just now - and for pretty good reasons, in my view. Recently, I found myself at his recent 'Violent Amnesia' exhibition, at Kettle's Yard, in Cambridge's, with my friend, Tim - and came away feeling invigorated by what we saw.

|

| Oscar Murillo, '(Untitled) Catalyst', Oil & Graphite On Canvas, 2018-19 (Detail Below) |

|

| Oscar Murillo, '(Untitled) Catalyst', Oil & Graphite On Canvas, 2018-19 (Detail Below) |

Murillo is an ex-patriot Columbian artist - from pretty humble origins, it would seem. He studied in Britain, following his family's relocation, and has continued to made something of a base for himself here. However, as would seem to be the case with many artists, these days, he seems to wander the globe relentlessly - seeking creative impetus, making cultural and conceptual connections, and collaborating, wherever it seems most appropriate to do so. Certainly, ideas about migration, displacement, the complex and fluid, relationships between physical and mental territories - and about the friction between community and globalisation, all appear to form key thematic underpinnings to the work. Indeed, Murillo has talked quite openly about borders, and the physical domains they delineate, as something he experiences largely through the window of a plane - his ideas and emotions flowing more universally, on the way to somewhere else. If nothing else, the wide-ranging scope of his practice feels like a inspiring antidote to the growing and depressing trends of nationalism and intellectual or imaginative restriction - against which any self-respecting artist must surely stand opposed, these days.

|

| Oscar Murillo, 'Violent Amnesia', Vinyl Cut Letters & White Paint On Wall (Site Specific), 2019 |

The Cambridge show alluded to this early on. The first, eponymous piece encountered, was a text-based memorial to a dead friend, which pleased me greatly with its use of vinyl cut lettering, applied directly to the wall - and partially obscured by a slew of gestural white paint. However, that almost feels like an adjunct to the main show, which really began with a forbidding curtain of dark, roughly collaged canvas pieces, obscuring one's view of the work beyond in two directions. This was actually the first instalment of Murillo's long-term project, 'The Institute Of Reconcilliation', which reappeared throughout the exhibition, at recurring intervals. Here, it seemed to serve as a physical, as well as a visual obstacle to be overcome - suggesting to the seeker of artistic refreshment, "You must struggle to make any progress here." Is this not also, in essence, the all-too-common experience of that quintessential twenty-first century figure - the migrant?

|

| Both Images: Oscar Murillo, '(Untitled) Catalyst' Paintings, With 'The Institute Of Reconciliation' (Installation), Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, June 2019 |

Behind this, in one room of the impressive new Kettle's Yard exhibition space, hung a thrilling suite of Murillo's ambitious '(Untitled) Catalyst' paintings, alongside another phase of 'The Institute of Reconcilliation' (combining more tattered canvas drapery, damaged church pews, and a concoction of burnt corn and clay). The latter appears to employ culture-specific references to the Colombian working classes, amongst other things, and is engaging enough. However, with my painter's hat on - I'd be lying if I didn't admit it was the 'Catalyst' pieces that really blew me away, in that particular gallery.

|

| Oscar Murillo, 'The Institute Of Reconciliation', Oil On Canvas, Steel Rail, Church Pews, Burnt Corn & Clay, 2014 - (Ongoing) |

It occurs to me that it's increasingly rare to encounter this kind of ambitious, freely expressive, abstract painting in a contemporary exhibition, nowadays. Nevertheless, it's still one of the most profound thrills in art, to be confronted, all over again, with someone's attempt to discover exactly how paint might get from one edge of a flat surface to another, with energy and verve. Walking into this room was, for me, an experience not too far removed from that of engaging with Gerhard Richter's timeless 'Cage' suite, at Tate Modern.

|

| Oscar Murillo, '(Untitled) Catalyst', Oil & Graphite On Canvas, 2018-19 |

Like much of my favourite painting of this kind, the 'Catalyst' pieces manage to combine overall simplicity (at first sight), with almost infinite, multi-layered complexity - revealed as one stares into their depths. Composed of tangled overlaid networks of scribbled marks, and broader veils of dragged colour, they achieve an imposing degree of monumentality, whilst also operating on a very human scale by obviously recording of the gestures of the hand and arm. Indeed, they relate us to our infantile, attempts at clumsy, intuitive picture-making, even as they exist as mature and deeply reflective paintings. This is, of course, essentially what the Abstract Expressionists were attempting, seventy-five odd years ago. It's exhilarating to witness it being revived as an approach, with such verve and commitment, so deep into the Twenty-First Century.

|

| Oscar Murillo, '(Untitled) Catalyst', Oil & Graphite On Canvas, 2018-19 (Detail Below) |

That these paintings constitute a related series is evident not just from their shared and restricted palette of reds, blues and blacks (somewhat reminiscent of ball-point pens - I now realise), but also from the method of their execution. It transpires that Murillo's method here involves laying one canvas over another - loaded with paint, before scribbling through from behind. They are thus a species of turbo-charged mono-printing, as much as they are paintings in the traditional sense, and clearly evolve out of each other. That the list of media employed includes graphite, emphasises that they are also drawings as much as paintings (if all that tangled calligraphy hadn't already proved the point). It's no secret that I'm a sucker for a good series - and for such hybridised forms of media-transference.

|

| Oscar Murillo, '(Untitled) Law', Oil, Oil Stick & Graphite On Canvas & Velvet, 2018-19 (Detail Below) |

Murillo's willingness to flit between modes of expression, even within the arena of wall-based picture-making, was underlined in the neighbouring gallery. The paintings exhibited here combine much of the same expressionistic freedom, and indeed - an overall scruffiness which is thoroughly refreshing in these over-designed, digitally manipulated times. Here though, Murillo also combines his painterly gestures with stencilled, screen printed and more carefully drawn motifs, as well as elements of scrawled text. That he is a collagist too, is clear from this piling up of random, and possibly more symbolically freighted statements. It's also made explicit in the means of physical construction often employed. It transpires that many of his paintings are literally stitched together from separate sections of canvas - much as is the case with the draped pieces already encountered.

|

| Oscar Murillo, 'Violent Amnesia' 'Oil, Oil Stick, Graphite & Screen Print On Canvas & Linen, With Steel Rail, 2014-18 (Detail Below) |

|

| Oscar Murillo, 'Untitled', Oil On Canvas & Linen With Steel Rail, 2015-16 (Detail Below), With: 'The Institute Of Reconciliation' (Detail) |

The interrelatedness of all this is evident in the painting which again shares a title with the entire show, and which is constructed to hang, curtain-like from a steel pole. Meanwhile, in a far corner, the (for me) most pleasing of Murillo's ragged canvas drapes ('untitled') obscured a window - content to revel in its pure grubby materiality, without carrying any imagery at all. In such a fashion, Murillo gets from Rauschenberg to Eva Hesse in a single, effortless bound. But if this weren't enough, his most dramatic intervention in this particular room - another iteration of 'The Institute of Reconciliation', proves his trans-media credentials, once and for all. Here, a vast avalanche of seemingly filthy canvas sections, resembling discarded industrial tarpaulins, spilled across the floor. The wall beyond,was defaced by a field of oily scuff marks - suggesting the canvas was dragged across it in the most rudimentary form of abstract image-transfer imaginable. The inclusion of more burnt clay, corn, and coins here alludes to the already mentioned thematic underpinnings, but I'd have been more than content with it as a more ambiguously process-driven statement, to be perfectly honest.

|

| Oscar Murillo, 'Surge', Oil, Oil Stick & Screen Print On Canvas & Linen, (2017-18) With: 'The Institute Of Reconciliation' (Detail), |

|

| Oscar Murillo, 'The Institute Of Reconciliation', Oil On Canvas, Coins, Burnt Corn & Clay, 2014- (Ongoing) |

Indeed, if I have any criticism of Murillo's practice (or the small taste of it revealed in Cambridge), it is only that his seeming attempt to cover all bases, formally and conceptually, must inevitably fall a little flat eventually. For me, this occurred next door, in the tiny St Peter's church. The ever-expanding 'Institute..' continued here, featuring some pretty rudimentary papier mache figures, punctured by sections of metal ducting, and perched on yet more damaged church pews. The accompanying notes reveal these to be reminiscent of yet more ritual sacrifice - in this case, the Colombian 'Mateo' effigies, traditionally burnt at New Year. Murillo's intention with these, as with all his burning of clay, corn, and scattering of coinage, seems to be to comment on the exploitation of labour and destructiveness of consumption. That's laudable enough, but again - I feel like the impressive formalist aspects of this multi-facetted installation somewhat overwhelm the socio-political content it purports to carry. Ultimately though - who am I really, to criticise another, far more accomplished artist, for attempting to pack in too many things all at once?

|

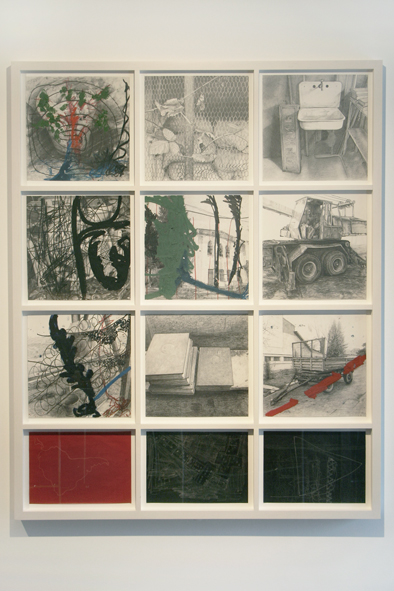

| Oscar Murillo, 'Organisms Of All Countries Unite', Graphite, Oil Stick & Coloured Pencil On Paper With Carbon Paper, 2016 (Details Below) |

And that Oscar Murillo is actually able to cash most of the cheques he writes, was revealed in a couple of smaller spaces, upstairs at Kettle's Yard. 'Organisms From All Countries Unite', comprises four composite suites of meticulous drawings, over which are imposed abstract gestures in a far cruder hand. The drawings, it transpires - are executed by another artist, commissioned to work from photographs taken by Murillo, to document the economic decline of the once-prosperous (in Soviet times) Azerbaijani village of Sheki. The gestural defacement was then committed by Murillo - in a piece of disruptive collaboration of which I thoroughly approve. It feels like a far more eloquent attempt to reconcile visual expressiveness with a socio-political theme somehow - perhaps because of the inclusion of explicit representational imagery, and the conflict between two authorial voices.

|

| Oscar Murillo, 'Organisms Of All Countries Unite', Graphite, Oil Stick & Coloured Pencil On Paper With Carbon Paper, 2016 (Detail Below) |

Also upstairs, hung another collaborative statement, in the form of the mixed media piece, 'Frequencies'. This represents an on-going project, in which Murillo encourages school students to carry-out free-associative drawings on pieces of canvas, wherever his international travels take him. These are subsequently stitched together in the form of yet more stitched drapes - potentially giving voice to all the world's children, I suppose. For such an ambitiously outward-facing, and engaged artist, that seems like a perfectly appropriate ambition. And after all, if it's not an artist's job to cut creatively through all the barriers of inequality, misunderstanding, and isolationism, currently besetting us all - whose is it? Oscar Murillo seems admirably up for the task.

|

| Oscar Murillo & International Students Aged 10-16, 'Frequencies', Mixed Media, 2015 (Part Of Long-Term Collaborative Project) |

Oscar Murillo: 'Violent Amnesia', ran 9 April - 23 June 2019, at Kettle's Yard, University Of Cambridge, Castle Street, Cambridge, CB3 0AQ.

Oscar Murillo: 'Manifestation' runs until 26 July 2019, at David Zwirner, 24 Grafton Street, London, W1S 4EZ