THE P-WORD:

Like many other folk these days, I drop the word 'psychogeography' with careless abandon. Indeed this blog is littered with it, as are many others, along with numerous books, articles, films, lectures, seminars, websites, tweets, - and who knows what else? It's a term (perhaps like 'Hauntology') which describes a recognisable sensibility within certain cultural expressions, but which has inevitably become devalued through its over-application to a increasingly diverse range of artefacts and activities.

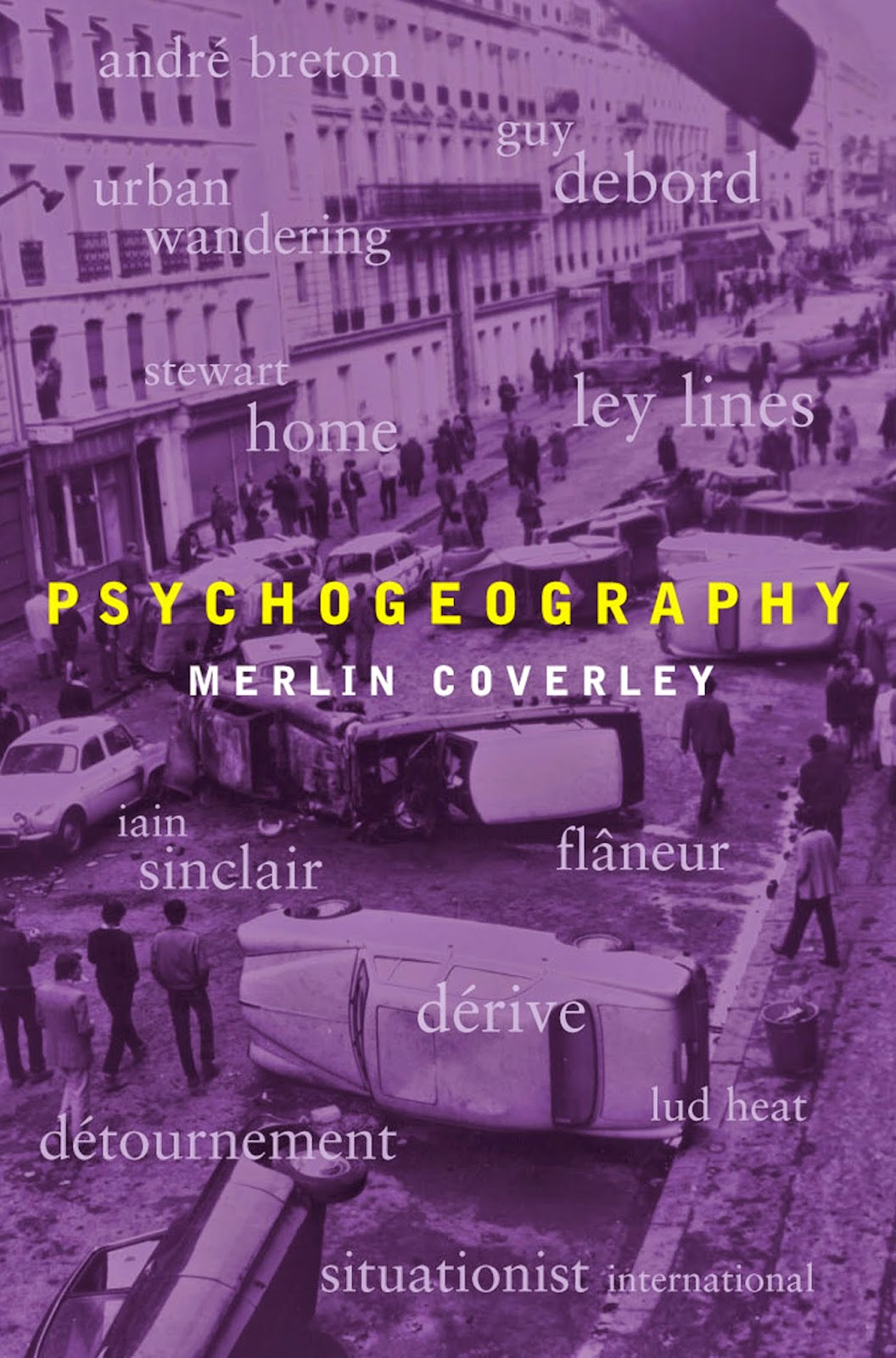

Of course, it's not unusual for such invented, theoretical labels to become adapted to different uses and often disputed over, in the process losing any currency they may have once had through dwindling specificity or changes in intellectual fashion. I don't want to embark on an extended discussion of the word's multiple applications and provenances here, but would once again refer anyone interested in the Psychogeographic tradition to Merlin Coverley's useful little overview, 'Psychogeography' [1.]. In his introduction, Coverley himself states,

'Psychogeography'. A term that has become strangely familiar - strange because, despite the frequency of its usage, no one seems quite able to pin down exactly what it means or where it comes from. The names are all familiar too: Guy Debord and the Situationists, Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd, Stewart Home and Will Self. Are they all involved? And, if so, in what? Are we talking about a predominantly literary movement or a political strategy, a series of new age ideas or a set of avant-garde practices? The answer, of course, is that psychogeography is full of all these things, resisting definition through a shifting series of interwoven themes and constantly being reshaped by its practitioners." [2.]

|

| Self-Styled Comic Book Magus, Alan Moore |

In the light of this, I was interested to see that Iain Sinclair, a writer who many may see as sitting at the head of the table of literary psychogeography, now appears to reject the term altogether. This was made plain to me whilst reading the Quietus article, (already referred to in one of my subway-themed posts), in which comic book writer, Alan Moore, discussed his own psychogeographical interests in relation to Sinclair.

"Perhaps understandably, Sinclair has more recently attempted to distance himself from the term psychogeography. In the film, 'The London Perambulator', Sinclair urges that psychogeography had relevance when the Situationist used it as an aggressive way of dealing with the city, and then again when Stewart Home later resurrected it and brought comedic value to it, but eventually became a 'nasty brand name' used to describe almost anything to do with cities or walking. He has instead signed up to Nick Papadimitriou's notion of 'Deep Topography' which brings the tradition back to that of the British naturalist, the wanderer of edges who is not so preoccupied with the concept of his practice." [3.]

|

| Iain Sinclair |

To be honest, I'm happy to leave the semantic debate hanging. Suffice it to say, for my money, 'Deep Topography' is a perfectly pleasing term - if no more or less useful than the term Sinclair is keen to replace. Instead, the Quietus article led to me consider two other questions. Firstly, who exactly is Nick Papadimitriou? Secondly, why did it take me so long to get round to watching 'The London Perambulator'?

PERAMBULATOR:

|

| Nick Papadimitriou. Still From John Rogers (Dir.), 'The London Perambulator', 2009 |

'The London Perambulator' is a documentary film, made in 2009 and directed by John Rogers. It takes as its subject the activities of outsider/Deep Topographer, Nick Papadimitriou, a man who, (even more than any of the other names dropped here), could be labelled a genuine and rather marvellous eccentric. Certainly, his whole life now seems to be subsumed into an endless cycle of wanderings and detailed explorations of those parts of Middlesex that most people would automatically overlook. His chosen patch is archetypal Edgeland territory, with all that that implies. The film includes significant contributions from Iain Sinclair, Will Self, (for both of whom he has worked as a researcher in the past), and, slightly surprisingly, comedian, Russell Brand.

|

| Comedian (And Self-Styled Revolutionary/Sex Machine/Media Messiah), Russell Brand |

|

| Nick Papadimitriou: Reading Between The Lines. Still From: John Rogers (Dir.), 'The London Perambulator', 2009 |

Perhaps Sinclair and Self's disillusionment with the label often attached to them, stems in part from comparing the depth of their own activities and relationship to the landscape with that of Papadimitriou's. If they ultimately re-examine their own experiences through the detached filter of literature, there is a sense in which Nick is Deep Topography [5.]. It's one thing to sense physical underground streams and discuss how the engineering of such natural flows into the fabric of the city lends it a multi-layered aspect, (as the film opens), or to exhibit an obsessive interest with the Mogden Water Purification Plant [6.]. However, it is something altogether different to claim, "my ambition is to hold my region in my mind", as he does later, and to imagine his own identity becoming totally subsumed into the very fabric of Middlesex. For all his apparent superficialities, it may be that Russell Brand's slightly daffy air of wonder at encountering someone so singularly at one with his chosen subject, comes closest to pinning down Nick's essence. Maybe this isn't really a surprise after all. Brand is known for his quasi-spritual dabblings, and there's definitely something of the ecstatic mystic about some of Papadimitiou's utterances. He would appear to come from Blakeian tradition more than a Debordian one.

[1.], [2.]: Merlin Coverley, 'Psychogeography', London, Pocket Essentials, 2006

[3.]: John Rogers (Dir.), 'The London Perambulator', London, Vanity Projects, 2009.

[4.]: I have no knowledge of Sinclair's previous experience in this respect. He's associated with plenty of counter-cultural figures over the years though, including notorious 'importer' Howard Marks, so I doubt he's a complete naif.

[5.]: I think I'm talking about degrees of intensity and emotional commitment here. Papadimitriou is, after all a published author too:

Nick Papadimitriou, 'Scarp, In Search Of London's Outer Limits', London, Sceptre, 2012.

[6.]: Papademitriou's linkage of The Sewage Works' processing of externalised waste, with the impulse towards psychotherapy, is exactly the kind of thinking many of us lapsing into at any opportunity, (although not quite so passionately expressed, perhaps). And, this focussing on what Self splendidly calls forgotten "Oxbow Lakes Of Urbanity", is little different from hanging around in Leicester's subway system, after all.

[7.]: John Rogers (Dir.), 'Inside Deep Library', London, 2007